PRACTICE AREAS

PRODUCTS LIABILITYS - PERSONAL WATER CRAFT

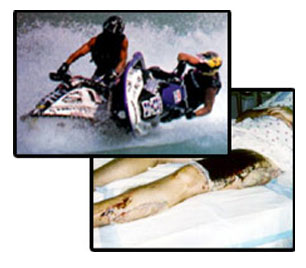

On August 28, 2000, at approximately 2:45 pm, Mr. William Steen, while operating a 1998 Bombardier Sea-Doo on Lake Jordan in Elmore County, Alabama, was violently struck in the right leg by another 1998 Bombardier Sea-Doo that lost steering control when the operator, William Petty-Fitzmaurice, let off the throttle and attempted to turn the vessel away from Mr. Steen’s vessel. The impact severed Mr. Steen’s right leg below the knee.

Tragedies similar to Mr. Steen’s occur thousands of times a year and will likely increase as the number of personal watercraft continue to grow. The greatest tragedy, however, is that many of these accidents can be avoided. As the personal watercraft industry grew, competition intensified into a race to build the fastest and most powerful personal watercraft in order to maximize sales. The industry’s marketing was successful. It is estimated that number of personal watercraft in use has grown from under 100,000 in 1987 to over 1,200,000 today. But the number of accidents has also steadily increased.

By the late 1970s, increased reports of personal watercraft accidents were a matter of concern, and by the early 1980s, had become a major concern for marine enforcement agencies. In May 1998, the National Transportation Safety Board (“NTSB”) addressed many of the safety concerns arising from the increasing use of personal watercraft and recommended that the industry and Coast Guard take affirmative steps to address the problem. Sadly, this call for action has largely gone unanswered, as the personal watercraft industry has put profits ahead of safety.

WHAT IS A PWC?

A. Personal Watercraft Defined.

To many people, the term “personal watercraft” is a foreign expression. Personal watercraft (“PWC”) are Class A inboard boats, powered by two-to-four stroke gasoline engines. They do not have propellers, but rather use a water jet pump for propulsion.

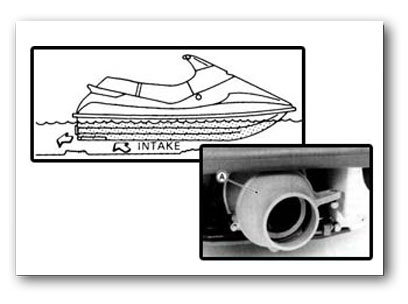

B. Jet Propulsion.

The PWC jet propulsion system works very similar to an aircraft jet engine. Water is taken in through intake valves and is concentrated, accelerated, and expelled through an output valve at the rear end of the craft.

In contract to aircraft engines, however, a PWC is both powered and steered by the water jet. There is no rudder like on planes or other boats. The moveable nozzle is directed and the thrust of the water principally controls the direction of the vessel. The current PWC models also do not employ propulsion systems that can reverse their thrust for braking purposes, like planes and some jet boats. The operation must either allow the vessel to coast to a stop or do a controlled spin.

C. Various Models and Speeds.

The PWC industry is dominated by five different manufacturers: (1) Kawasaki ("Jet Ski"), (2) Yamaha ("WaveRunner"), (3) Bombardier ("Sea Doo"), (4) Polaris, and (5) Honda.

The first personal watercraft model was introduced in Canada in 1968 by Bombardier. Kawasaki later introduced the "jet-ski" in the United States in 1974. The original "jet-ski" model had a 32 horsepower engine and traveled at peak speeds of approximately 30 mph. The personal watercraft model required the user to stand upright, demanding practice and coordination to operate the vessel. Thus, the product was not an immediate success in the U.S. market. Since that time, the number and types of personal watercraft available to the public have grown dramatically.

The current personal watercraft models contain engines with 200 h.p. that can accommodate from one to three riders, and can achieve speeds in excess of 65 mph. In addition, approximately ninety-eight (98%) per cent of all personal watercraft are the sit-down variety in which the operator and passenger(s) are seated on the vessel, instead of standing or kneeling on the product. This design modification significantly reduces the skill and expertise required to operate the vehicles, making the current personal watercraft models more accessible to consumers of all ages and levels of experience.

WHY ARE PWC UNREASONABLY DANGEROUS?

A. Personal Watercraft Statistics.

It is undisputed that PWC are the most dangerous watercraft in existence.

"Although comprising only 2 per cent of the current series, personal watercraft fatalities across the United States have increased dramatically over the past decade, from 5 deaths in 1987 to 57 in 1996. This 1,100% increase is almost certainly related to the marked increase in the number of personal watercraft on the nation's waterways as well as the significantly increased speeds these craft are capable of achieving. Perhaps this explains why personal watercraft operators are injured 8.5 times more often than those operating other motorized watercraft. "

B. Manufacturers Have Over-Promoted The Vessels To Inexperienced And Inadequately Trained Operators.

When evaluating whether a product like a PWC is unreasonably dangerous, the target audience and foreseeable use of the product must be considered. Unfortunately, PWC manufacturers have traditionally focused their massive marketing budgets on the very young and inexperienced. According to the National Transportation Safety Board's 1998 study, the vast majority of PWC operators involved in accidents were between the ages of 12 and 21. Many of these operators viewed the high performance vessel as a "toy." But personal watercraft are not toys, and people must realize that a 12 year-old child is simply not equipped to handle a 135 horsepower vessel traveling at speeds in excess of 65 mph. Nevertheless, legislatures have been slow to enact universal and effective legislation for PWCs.

By far the most prevalent type of accident involving personal watercraft are PWC collisions with other vessels. In 1989, the National Association of Boating Law Administrators issued the Final Report of The Personal Watercraft Subcommittee. The report concluded that approximately 80% of the personal watercraft accidents were collisions.

Collisions were also the leading cause of fatalities. Nearly ten years later the NTSB's May 1998 report confirmed again that the overwhelming type of accident pattern were collisions with other vessels. But in the interim, virtually nothing was done by industry to make the PWC designs safer. Accident data analysis further conclusively reveals that inattention, inexperience, and inappropriate speed were the leading causes of the accidents. Interestingly, alcohol was found to cause only a relatively small number of the accidents.

According to the National Transportation Safety Board's recent report, roughly eighty-four (84) percent of PWC accidents involved operators who had no boating safety education or instruction. In fact, seventy-three (73) percent had been riding less than an hour when their accident occurred. Forty-eight (48) percent of those injured had never operated a personal watercraft or done so only once. Therefore, it is clear that experience and lack of training are two of the major factors that have contributed to the recent epidemic of injuries and deaths among PWC operators.

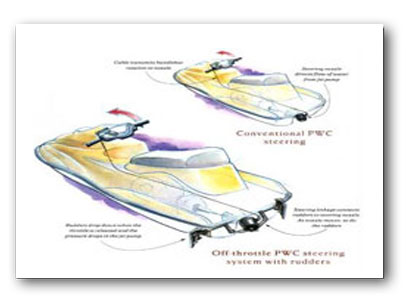

While implementing age restrictions and training requirements can improve the overall experience and ability of PWC operators, these steps do nothing to address the products' latent design defects. Perhaps the most dangerous aspect of a PWC is the lack of directional control when the throttle is released. The distinctive nature of the movable water jet, without a rudder or brakes, creates unique handling hazards. The industry has characterized this phenomena as "off-throttle steering." The description of "off-throttle steering"-an oxymoron-describes a situation where an operator instinctively releases the throttle when confronted with a dangerous situation in an attempt to avoid a collision. Once the water-jet is disengaged, however, the ability to safely steer is lost. The PWC essentially becomes a torpedo heading in the last principle direction of thrust.

At 40 mph, a PWC travels about 20 yards per second and can coast well over 200 feet. As speeds increase, the time available for operators to react decreases.

To make matters worse, PWCs are typically marketed as safe to be operated in close proximity to other vessels. But the time frame for tracking and reacting to other vessels can be quite limited under these situations. Operators of two PWCs traveling at 40 mph on a head-on course will have a response time of 1.3 seconds to travel 50 yards. Even when the vessels are converging at a 45-degree angle, the response time is less than 2 seconds. The response time must also accommodate perceiving the other vessel, deciding which vessel is burdened to comply with the navigational rules, the risk of collision, and the appropriate response.

Under these situations, the concept of actually accelerating the throttle in the face of danger, seems counter-intuitive to most inexperienced personal watercraft operators because it is opposite to the emergency use of controls of virtually every other type of vehicles.

Cars, ATVs, snowmobiles, and boats all have the ability to slow and turn when the throttle is released and the operator attempts to turn the vehicle. Thus, it is easy to understand why an operator, when confronted with danger, will instinctively release the throttle and attempt to avoid a collision.

Accident reports reviewed by the NTSB highlighted a "high risk of injury associated with personal watercraft." As a result, the NTSB made the following recommendation to the PWC industry and Coast Guard:

"Evaluate personal watercraft designs and make changes to improve operator control and to help prevent personal watercraft injuries. Consider items such as off-throttle steering, braking, and padded handlebars, and operator equipment such as personal flotation devices and helmets." (M-98-85)

"Develop with the U.S. Coast Guard, comprehensive standards that are specific to the safety risks of personal watercraft."(M-98-87)

"Determine within 2 years, through research, the feasibility of providing personal watercraft operators more control in an off-throttle steering situation." (M-98-88)

The deadlines have passed and none of the manufacturers have voluntarily recalled or retrofitted their products, or even issued any post-sale warnings. Instead, the manufacturers have been jointly studying the issues in the industry-dominated associations (SAE, NASBLA, ABYC, UL) that began evaluating these issues over a decade ago. Meanwhile the accidents, injuries and deaths continue to occur at an alarming rate.

PWC manufacturers have corrected the defective designs with controlled thrust designs and rudders.

Arctic Cat no longer manufactures PWCs, but its Controlled Thrust Design prevents the thrust of the engine from falling when the throttle is released and the operator has attempted to turn the vessel. Arctic Cat offered the design to industry for a lump sum payment of $25,000 and a royalty payment of a dollar a boat. The cost of producing the system is about $10.00 per vessel and the system was feasible as early as 1990. Kawasaki markets a similar device called the "Smart Steering System."

Most manufacturers have also developed rudders, tabs, and/or brakes to provide directional control when the throttle is released. These designs have been feasible since the late 1980's and are currently available on some Bombardier models.

One of the easiest, but perhaps the least effective means for PWC manufacturers to improve the safety, is to use improved warnings on the products. Under pressure from the U.S. Coast Guard, the industry has developed new warnings that clearly focus on the off-throttle steering hazard. Although the warnings were approved by the Coast Guard in 1999, they were not put into use until the 2001 models.

Finally, an important step in the evolution of PWC safety is the implementation of regulations requiring safety training and minimum age requirements for operators. Clearly, any vessel that can travel at 65 mph requires training and experience to operate safely. Yet only recently have states begun to enact training and age requirements. Inexplicably, many states have opted to set the bar rather low by adopting operational requirements of less than 100 feet between vessels, which are useless with the speeds of the vessels.

Examples of good PWC regulations can be found in Florida and New Jersey. Legislation in these states has proven that training truly does help prevent injuries. Consumer advocacy organizations and trial lawyers should continue to lobby their respective legislative bodies to enact these life-saving measures. Our society has long recognized the importance of training for drivers of automobiles; similar programs should be implemented to educate PWC operators on the unique handling characteristics and dangers associated with PWC use.

IV. INDUSTRY EXCUSES.

Blame The Victim, Owner, Or Operator.The PWC industry has one common response to products liability litigation involving its products - blame every one but themselves. Ironically, the manufacturer will often claim that the victim was "reckless" or "negligent" because they were operating the vessel at a high speed in close proximity to other vessels. This argument can be minimized in two ways. First, use the manufacturers own marketing to show how the company promoted wake-jumping, sharp turns, and the high-speed operation of the PWC in close proximity to other vessels. Second, carefully evaluate the Inland Navigational Rules, and their state counter-parts, to assess the comparative fault of all operators. See 33 U.S.C.A. § 2002-2016.

Causation.

As in any products case, causation must be completely explored in a PWC claim. Most PWC accidents involve more than one craft and thus more than one operator. Often, an operator will lose control and collide with another vessel. Sometimes, the PWC operator will have consumed alcohol. A detailed boating accident reconstruction is needed to quantify the orientation at impact and speeds of the vessels to properly establish that the design was causal and that an alternatively designed PWC would have minimized or prevented the collision or injuries

State of The Art.

"State of the art" is a defense commonly asserted in products liability cases and always used by PWC manufacturers. The manufacturers disingenuously argue that no alternative design was technologically or economically feasible, and that the proposed alternative designs would make the product more dangerous. These arguments ignore the fundamental tenet of products liability law - that products must continue to evolve. It is not enough that a manufacturer simply says, "nobody else has done it." Industry standards alone will not establish the "state of the art" defense. But counsel must be prepared to put the entire industry on trial to overcome this defense.

CONCLUSION

Products liability law has been at the forefront of insuring that products placed into the stream of commerce are continually developed and refined to adopt the safest designs. While no single design change or legislative action will prevent all injuries or deaths, an integrated effort to design safer PWC will no doubt prevent many injuries and save lives.